Bluesky’s Great Social Splintering

When Elon transmogrified Twitter into X and so shifted the vibes a couple of octaves to the right, an exodus of alienated users scoured the internet for a new home. They eventually landed on Bluesky. In contrast to X’s walled garden, Bluesky is built on the decentralised social network protocol, AT Protocol (or “ATProto”), which lets users carry with them their social graph and content across different platforms. By unshackling users from the tyranny of centralised platforms—the nature of which may change according to the whims of mercurial billionaire owners—they are collectively empowered to hold the platforms accountable. As Renee diResta wrote in a post on Bluesky:

The idea of one massive “public square” should be squarely over & dead by now -didn’t work, won’t work, can’t work. The whims of a billionaire shouldn’t be the rules. But on a centralized platform, they are. So here we are.

Free choice, that fabled cure-all, may seem like an apt solution to the vexing and oft-paradoxical challenge of governance in social networks. Yet, all the devils dance in the design. If adopted at scale, ATProto’s frictionless, cross-platform portability contains within it the threat of a negative competition environment, a classic Moloch, that may further splinter our social sphere, and drive the online conversation into even more extreme trenches.

Mundus sine Caesaribus

Jack Dorsey instigated in 2019 Bluesky as a project inside Twitter to build a decentralised social networking standard. Later Bluesky severed its ties with Twitter to establish itself as an independent social network built on the ATProto standard.

Today, there is momentum on Bluesky. It recently hit 37m users—still a couple of OOMs less than its competitors, but it’s not nothing. And the builder energy is palpable: projects are popping up left and right, TikTok and Instagram clones, services for analytics or feed customisation, Mark Cuban throws seed capital at some of them. Vibes are fun, it’s the good internet, good in the friendly-neighbour-kind-of-way with a sprinkle of furries. When CEO Jay Graber went on stage at SXSW wearing a t-shirt with the anti-Zuck slogan, “Mundus sine Caesaribus”, the t-shirt sold out in 30 minutes.

At its core, Bluesky is built up around a federated content system (colloquially called the fediverse), which is a way to distribute the network infrastructure across many nodes and operators, where anybody can set up a server to host content and users, while the content can flow between them. Crucially, users can move between different serves or services as they see fit, taking their content, connections, and followers with them. This account portability creates new incentive dynamics.

“The fact that users have that choice means we’re incentivized to keep serving [them] […] If a billionaire came in and bought Bluesky and took it over, or I decided tomorrow to change things in a way that people didn’t really like, then they could fork off and go on to other applications.” Jay Graber in The Observer

A rebalancing of power through platform fungibility. In short, good governance through a wise crowd. Thus the crux is this: what is the nature of that crowd’s collective decision-making, and how will this platform fungibility impact the communication ecosystem as a whole? A good place to start that enquiry is to look for rhymes in history. Here, the public internet itself might serve as a reference class: from the open nature of the TCP/IP communication protocol emerged a competitive environment that eventually pushed people into informational bubbles, and then into attention sinkholes where antisocial content curation created negative information spirals.

Islands of Ideology

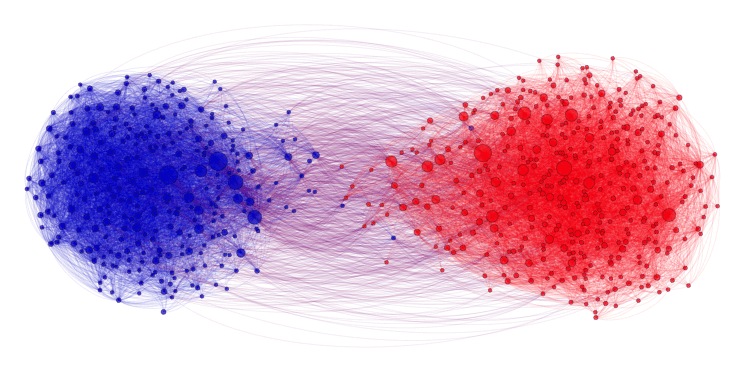

In the first wave of user-generated content, the Web 1.0, the hyperlink reigned supreme as a directed attention edge in the network. HTTP and HTML protocols made it relatively easy to create a small-scale static website, and so from one-to-many communications, we moved into more-to-many. Naturally, most of these websites and forums had trivial reach, if any at all, however, in aggregate, they began to matter. In the 00s, analysis of hyperlink graphs was all the rage. This graph from lada adamic was a classic:

On one side we have a cluster of blue nodes, densely connected, on the other a cluster of red nodes. Between the two clusters is a gossamer net of bridges. It’s a graph displaying the hyperlinks between websites of either conservative or liberal leanings in the US.

Structurally, the tea leaves were there to be read; the graph was the message. That topology could have been seen as a precursor to the splintered online information landscape of today. The epistemological reality in blue and the red cluster of the American political blogosphere is completely different: what is a self-evident truth on one ideological island would be deeply controversial on the other. I don’t think it’s hyperbole to state that this kind of information topology accelerated and exaggerated an existing trend in a splintering society.

In the Web 2.0 era, this informational atomisation continued. With Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, it became super easy to publish content, which then could be distributed to other users (mostly, on the same platform). Media moved from more-to-many communication to many-to-many information flows. These social networks became attention sinkholes. Curation and moderation of information became key to a successful platform experience, and the way to attract and retain users. The role of the information gatekeeper and curator moved from a professional class of scholars, journalists, and politicians, to a class of technologists, who implemented their (very human) priorities through algorithms that could operate at scale on those astronomical volumes of user-generated content. Those technology companies emerged and sustained themselves through ad-based revenue models that, generally speaking, relied on keeping eyeballs on the site for as long as possible. The best way of doing that is to meet the user’s tastes—even if those tastes favour short-term hedonist satisfaction over long-term health.

One doesn’t have to go full Sapolsky to state that humans tend to be generally geared towards hedonistic short-termism and that structures matter. There is less obesity in modern, capitalist Japan than in modern, capitalist USA, because the Japanese state took measures to implement nutritional policies that induced a healthy populace. If we move from nutrition to information, a similar dynamic appears: quality information is expensive to produce, slob is cheap. As such, cheap content will outnumber and outpace thoughtful and carefully crafted content by many, many miles. Not only is bad information cheaper to produce, if no longer tethered to truth, it’s much easier to make glitzy and seductive to our mammalian brains. We are attracted to shiny stuff. To the fat and sugars. The fantastic and crazy and triggering pull us in and steal one of our most valuable resources: our attention. Such is the race to the bottom of the brain stem.

Social networks are winner-take-all. The marginal cost of digital distribution is almost zero and it’s a non-competing good (i.e. one person consuming digital content doesn’t prevent another from doing the same, as opposed to, say, a banana). In this scenario, arguably, the only moat worth caring about is the network itself. This is why Reid Hoffman advocates blitzscaling. Every marginal user provides marginal utility to the network as a whole, and when it reaches a tipping point, the utility of the entire network (all users, the connections between them, and the content they’ve generated) feeds exponential growth. It makes sense, all things being equal, for a newcomer to join the biggest network, and thus the giants will outcompete the small. This is consistent with the observation that we observe a social media landscape dominated by a few gargantuan, continent-sized networks, who function a bit like sinkholes, sucking in users and attention and capital.

If other users are a given platform’s main utility for any specific user, then a platform switch comes at a high cost. All accrued network value is lost if you have to start building your network on a new platform from scratch. For a platform operator, it makes commercial sense to keep switching costs high, or rather, it doesn’t obviously reek of business wisdom to invest in lowering them. Removing offboarding friction leads to user leakage and will undermine the most critical value that the network has: you.

During the Web 2.0 era, much of the internet traffic flowed towards social media platforms, on which commercial pressures pushed the content into more and more extreme, while also pushing the operators to erect walls around their gardens to avoid user leakage. Now, Bluesky’s ATProto proposes to solve the former with a fix for the latter.

Defederate and Die

In the fediverse, cross-platform switching costs are reduced, and new types of incentive structures are likely to emerge from this design. I’ll attempt a Gedankeneksperiment to explore the implications.

Before we embark, a little caveat is in order: social network federation comes in many flavours, and the below presents a very simplified model of ATProto’s architecture, which, unlike the bridge demolition approach of ActivityPub, distributes the defederation process across several entities. Albeit this will be a simplification, I’d argue that the way the incentive dynamics are distilled holds true.

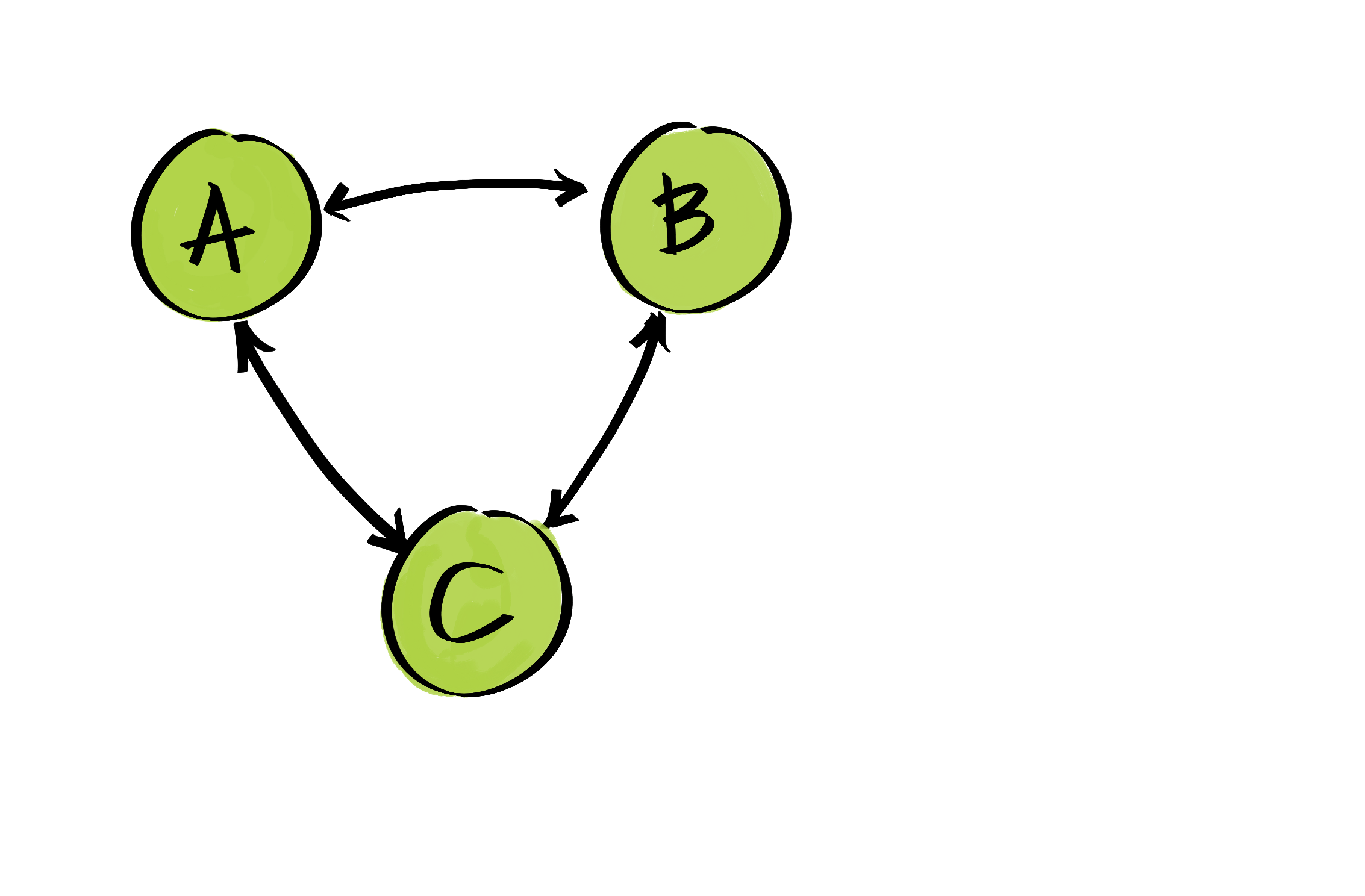

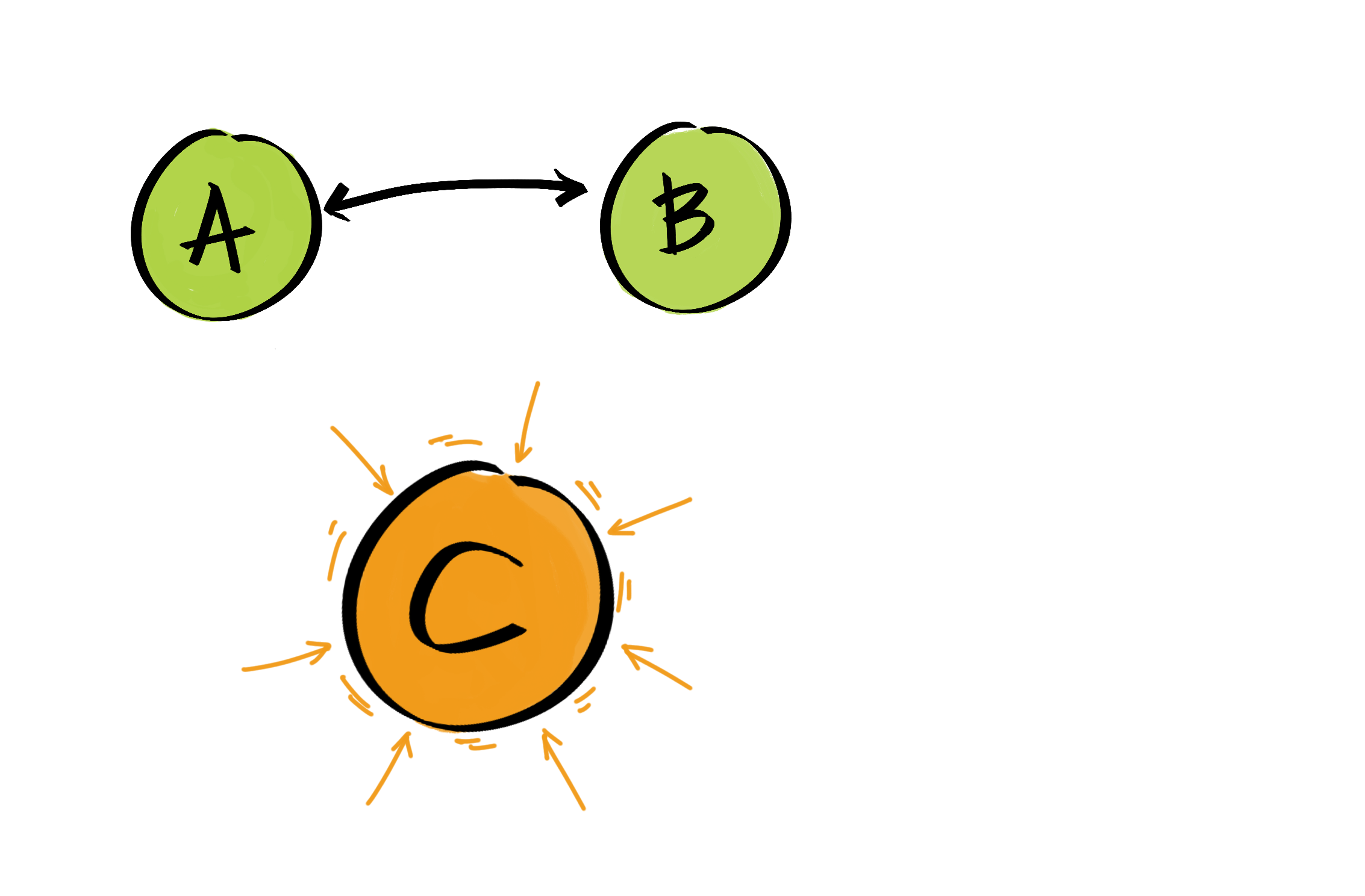

So, first, we can imagine a social network with three federated servers: A, B, C.

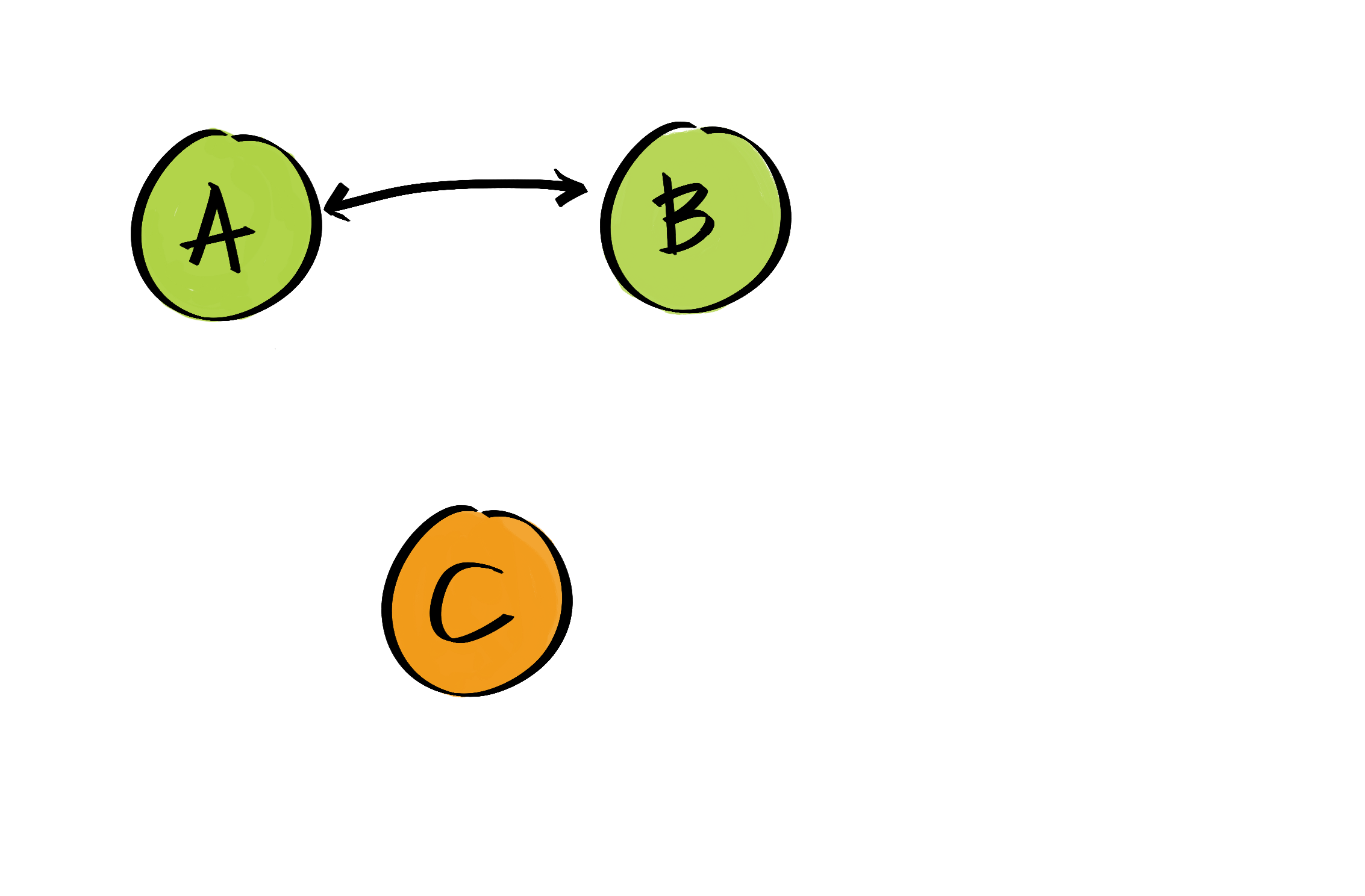

A and B are happy places: the content is generally moderate and benign. The vibes are good. C, on the other hand, is laissez-faire in their moderation, and to nobody’s surprise, conspiracy theorists start spewing the nonsense du jour. Users on A and B are upset, and ever diligent and willing to listen to their communities, the platform managers defederate A and B from C.

Users on AB stay happily ignorant of all the mess on C. However, C is a commercial venture that competes with attention sinkholes like TikTok, X, and Instagram. Money comes from showing as many ads as possible to their users, and they know that in order to reach a defensible market position they must blitzscale. So they tolerate or even (subtly) encourage incendiary content (space-laser lizards cabals, abhorrent beauty filters, etc.), and use every single dark design pattern they can without falling afoul of the law. Their island grows. Each marginal user brings marginal utility to the network as a whole; they scale. They raise more venture capital, and take a page out of the TikTok playbook with an aggressive marketing campaign on Facebook and X.

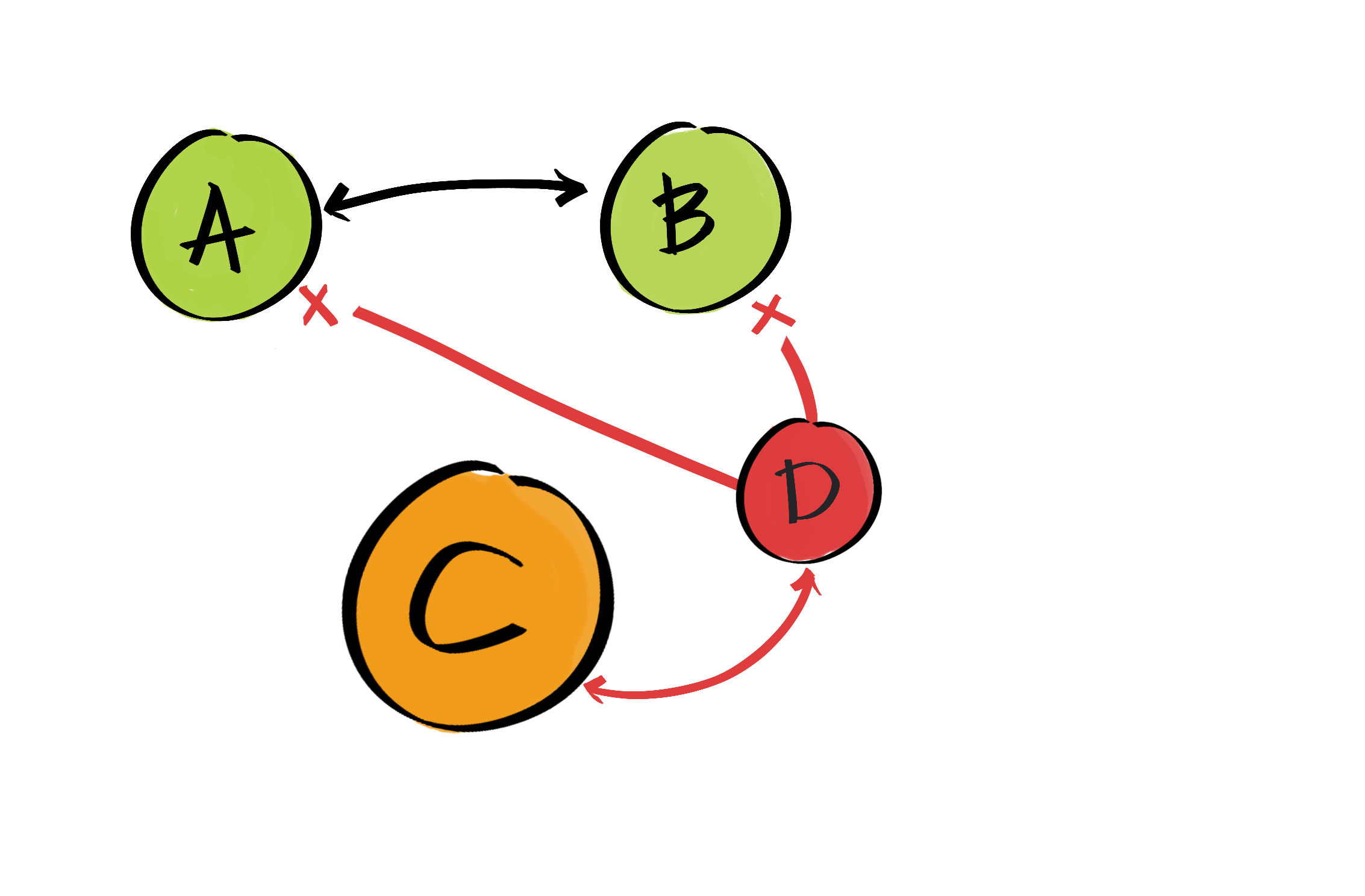

Now comes network D. Starting a new venture is all about peeling away the onion layers of risk. Location risk is certainly a key concern for a scruffy startup taking on the Goliath. One of the first layers of risk, after having gotten some whiff of product-market fit, is simply to get significant traction, and it’s a facile business decision to be where there is higher user flow. Put the store on the high street, not in the back alley. They like ATProto, as this is a way to usurp users from other networks. D decides to federate with A, B, and C, but in order to compete with the biggest network, C, they implement even worse incentive structures. Their network is basically a digital Fentanyl casino. AB defederates at kneejerk speeds.

Users on C can easily move their social graph to the new network, so now C is forced to further relax their moderation policies and explictly introduce brainrot waifus, the mukbang world championship, and so on. Together, CD now race at breakneck speed towards the bottom of the brain stem. AB stays happily ignorant, and entirely, completely, totally irrelevant. Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world. Tristan Harris makes another documentary. Sociologists, media theorists look on in horror.

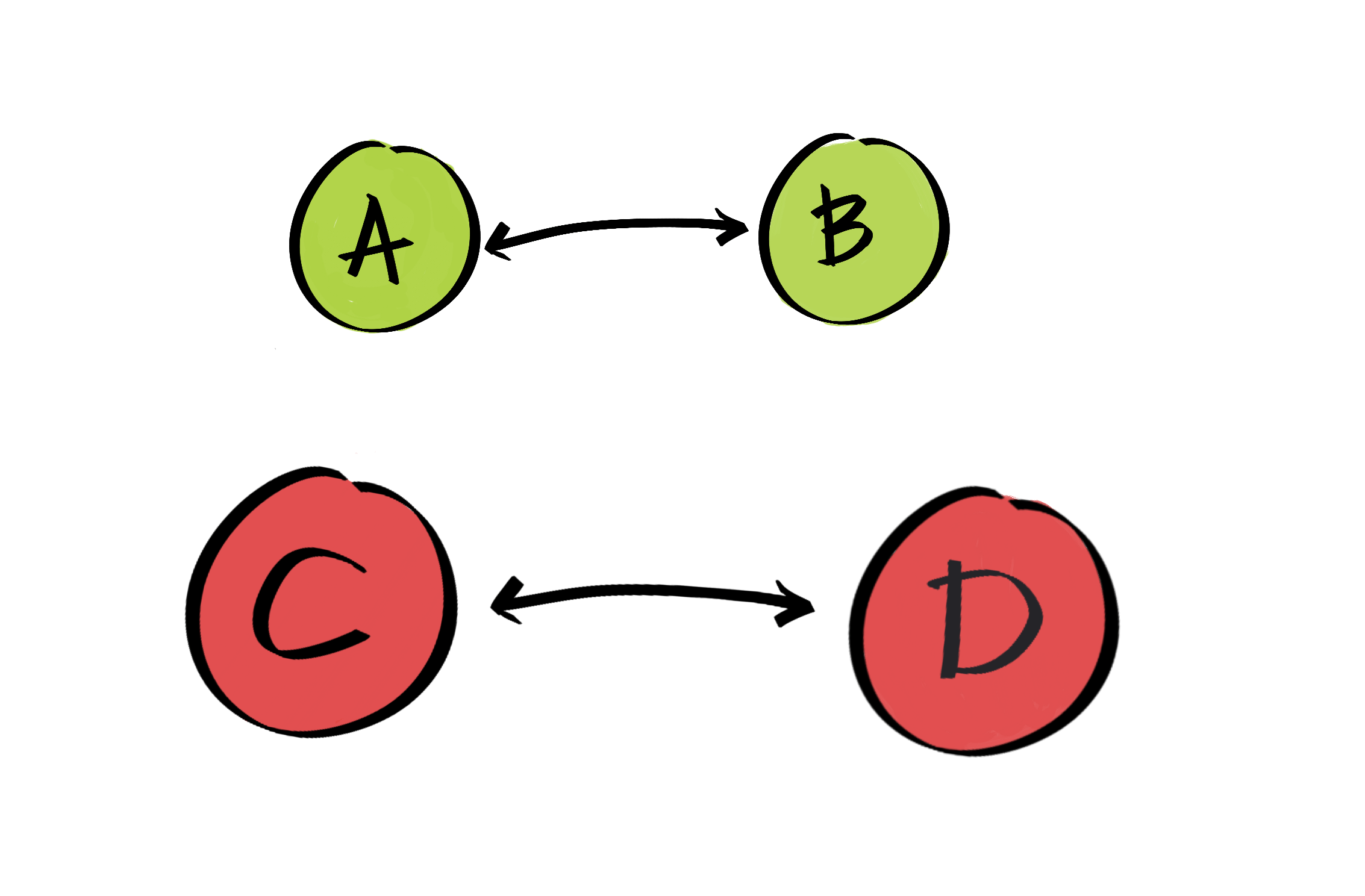

Then another social media platform, E, arrives… and the cycle repeats. Ad nauseam. The likelihood that a new network or user would join CD over AB is significantly higher, unless they have some kind of political bent that justifies going for smaller networks (or perhaps, more furry-friendly). In the end, the informational and ideological world on AB and the world on CD looks entirely different. CD is slob, cheap conspiracies, bad logic, in short, Postmanian mortal entertainment. AB, bless ’em, might be healthy places, their users frolicking around in peaceful pastures, that are in the social and political fringe, and as such bear little consequence on the public discourse or the future of humanity.

Decentralised Glitz is Still Glitz

Bluesky claims that account portability will let the collective behaviour of users keep the platform operators in check. By removing the barriers to social network switching, users can vote with their feet. Yet, unmitigated this platform fungibility comes also with a threat of worsening an already poor informational incentive landscape.

Clearly, we don’t want a centralised public sphere that can only contain one or two narratives. In the past, when trust in journalism was high(er), it was only because those who bought ink by the barrel became informational suzerains, the gatekeepers of a fabricated truth. Today, the propaganda is executed via algorithms and platform design under the auspices of centralised social networks, and it seems reasonable to assume that smaller, more user-controlled networks might mitigate some of the centralisation risks.

Yet, it should similarly be clear that a decentralised system that facilitates the frictionless and fast movement of content and users between platforms opens up another type of platform competition, which will almost certainly undermine the production and distribution of high-quality information, but rather let glitz explode all over the place like confetti. As AI joins the public conversation as content producer, curator, moderator, perhaps even consumer, we should expect this trend to accelerate even faster. All it takes for this hypothesis to hold is, I believe, that, one, the human psyche generally prefers the simple, fast, and glitzy, over the slow, healthy, complex, and, two, the most successful online media businesses will be the ones that capture most eyeballs for the longest periods of time. If both axioms indeed hold true, responsible designers have a duty to consider how the competitive dynamics of platform fungible systems like ATProto will impact the societal capacity for sane discourse.

For now the jubilant Bluesky community delight in the construction of a viable alternative to X, but in the distance looms an unresolved question—and, so far, a proper analysis of the incentive structures produced from ATProto’s design is relegated to the sidelines of the conversation. I’m on Bluesky, I want Bluesky to succeed. Online social platforms, correctly constructed, are great information networks that can produce and distribute knowledge for a better world, a world of more understanding and collaboration, and may even starve off the bellicose mares that again seem about to spring from their gates. However, I believe serious thought needs to go into the incentive dynamics that will emerge from ATProto’s platform fungibility. It’s not a question of left versus right, it’s about fast versus deep. About something that approaches truth against something that pursues clicks. Right now, I don’t have any suggestions for how to mitigate the risks herein highlighted. All I hope is that as the development and adoption of ATProto continues, we can have a clear-eyed conversation about the path ahead.